I play a lot of games.

That's a huge understatement, of course. I've got a stack of four DS games sitting in arm's reach, I've got a stack of six console games sitting over my by TV, I've got at least four games on the PC that are queued up to play, and if UPS would show up already I'd have three PSP games also. (And another DS game, and three more console games.)

Partly, of course, I play games because they're fun. This should go without saying, considering the focus of this journal, but even in this industry it's untrue surprisingly often. (I can't help but think that anyone in this industry who doesn't really love games is insane to be here, judging by the work hours and the pay. That's another post altogether though.) But I also play games for research. I can tell you what PN-03 did wrong. I can describe, in detail, why I think the Halo series was such a success, and only part of that is Microsoft/Bungie marketing. I can really ramble on at great extent on why save points are both irritating and absolutely crucial for any kind of suspense, and, in fact, at one point I was considering writing a Gamasutra article on that subject which never actually got finished.

It's sort of hard to figure out where to start with all of this.

Finally, however, I've figured out where to start. Ironically, I figured this out about one day before Greg Costikyan talked about people producing something similar to what I intend to, which makes it hard to take credit. But it's simple.

I play games partially to learn from them. As I play games, I'll write about what I've learned, what I'd do differently, and what I thought was fantastic.

These aren't reviews, so I'm not calling them reviews. I'm not going to say, at the end, that a game's score was 74.3% which places it at the top end of "Mostly Good Games" but not quite into "Games That Are Slightly Better Than Mostly Good, But Not Quite Really Good". I might, at most, recommend that people play certain games and avoid others, but these recommendations won't be based on how good the game is, they'll be based on how interesting the game is from a design perspective. Sometimes the worst games teach us the most. (Oh, how you'll get tired of me talking about PN-03.)

These also aren't criticisms. They're probably closer to criticisms than reviews, but I'm not entirely sure what critcism is. It doesn't seem that anyone really knows – Metacritic should probably be called Metareview, if we assume the two are different, but they're hard to separate. When I think "critic", the first thing that comes to mind is the hideously stereotypical French modern art critic, and I really don't want to be associated with any part of that.

In the end I've settled on calling these dissections. It's the most appropriate term. I'll be taking these games, pulling them apart as best I can, and describing all the interesting little squishy bits I encountered on the way. These are not guaranteed to be spoiler-free, though I'll try to mention when a major spoiler is coming up. Still, if you hate spoilers and plan to play the game, I recommend just skipping the dissection entirely (or rather, bookmarking it and coming back to read it later. Sending it to your friends would be appreciated also.) I will mention this at the beginning of every dissection, just to make sure it doesn't get forgotten, and I'll give some basic facts on the game at the beginning as well.

So, for my first dissection, we have . . .

Professor Layton and the Curious Village

Developer: Level 5

Developer's other notable games: Dark Cloud, Jeanne D'arc

Completion level: 100%

And, of course, the obligatory Penny Arcade strip.

THIS DISSECTION IS NOT A SPOILER-FREE ZONE. Read at your own risk.

Professor Layton is a puzzle game. Phrases like "primarily" or "first and foremost" simply don't apply, because Professor Layton is purely, 100%, a puzzle game. The gameplay is simple. You walk around the town of St. Mystere talking to people and examining suspicious objects. As you do this, you are shown puzzles. You solve them. Once in a while, someone advances the plot, unlocking more puzzles, more locations, and more plot. There are no action sequences, there are no time limits, there is nothing whatsoever to interfere with your contemplation of the puzzles. It is a very pure game, in that sense.

Art and Feel

The art style reflects this beautifully. I inevitably end up comparing art of this style to Tintin – it's clean and innocent, and while you may get the sense that there is evil lurking beneath the surface, it will certainly be vanquished well in time for tea. Layton himself is the perfect wealthy, honorable, British explorer archetype that never actually existed, with a mansion in the country that he rarely stays in, traveling from city to city in strange lands with a plucky assistant, having wild and yet somehow simultaneously sedate adventures that never leave you doubting who will eventually prevail. (It's the good guys, of course. But don't worry. The bad guys will escape and return again, and nobody will actually end up dying, ever.) This archetype may have started with Sherlock Holmes and I feel certain that Professor Layton and Sherlock Holmes would be fast friends within five minutes if they were ever to meet.

The game includes some FMV, and I was going to say that I didn't consider it particularly necessary, but thinking over it more closely it's actually just as understated and perfect as the rest of the art design is. Dialog-heavy console games can have issues providing a sense of how characters move and talk – Phoenix Wright gets around this by having extremely expressive sprites with exaggerated gestures and animation, Disgaea does much the same thing with equally-exaggerated single-frame pictures during dialog, Advance Wars: Dual Strike fails at this and honestly suffers for it, and Professor Layton pulls off a victory with its careful use of FMV. You never feel like you're watching a movie (or a recent Final Fantasy game, burn) but it sets the scene and the tone for each segment of the game wonderfully.

Tone is important for a game, and Level 5 nails this brilliantly. You're given the feeling that this entire town exists solely to provide puzzles for you and that it exists, in some sense, outside time. (I'll be revisiting this point, so don't forget it.) There's rarely any pressure on the player, and when there is it's gentle at best – people requesting your presence at your earliest convenience is about as pushy as the game gets. To make things even smoother, the game carefully leads you through the plotline. Whenever you're not actively in a puzzle the map screen contains a line of text telling you what to do next, from "Visit the park" to "Talk to Dahlia". I did run into a few cases where I forgot my goal and the text wasn't quite specific enough ("Talk to Beatrice" is unhelpful when you can't remember who Beatrice is) but even knowing that I'm supposed to be talking to a specific person is enough to narrow down your search significantly. You simply can't get lost in this game, and if you're stuck, it's because you're having trouble solving puzzles, not navigating.

That point is worth emphasizing, actually, as it's something I'm going to be bringing up frequently in these dissections. The player should never feel like he or she is fighting against the game. The player should always be fighting against the challenge, or the villain, or today's group of bad guys. There are cases where the interface is part of the challenge, but the controls should always feel smooth – there is a huge difference between "it's difficult to control my player" and "the player doesn't do what I tell him". Take a look at Steel Battalion for the first, and PN-03 for the second – Steel Battalion was difficult to control because you were controlling a giant robot with a three-foot long controller that had no less than five axes of movement, PN-03 was difficult to control because you couldn't jump left or right. (Why not? I still don't know.) It's a crucial difference, and Layton's interface does a fantastic job of staying out of the way from you and the puzzles.

The Puzzles

The puzzles are kind of a mixed bag.

It's nearly impossible to summarize the puzzles in any kind of useful way. There's 135 of them, and they range from matchstick puzzles to spatial analysis puzzles to word problems to the classic 8-Queens problem and many, many more. Whatever you're good at, it's probably in there, and whatever you're bad at, it's probably in there too. The vast majority of puzzles are technically unnecessary to beat and if it wasn't for a few points that require you to have solved a specific number of puzzles, you could likely get through the game with less than two dozen puzzles solved. You don't have to tackle the hard ones, unless you want to solve everything.

Unfortunately, some of the puzzle designs interact rather badly. First, a significant number of the puzzles are of the "Gotcha!" type. They reward you for thinking out of the box and finding the hole in the problem description rather than solving the puzzle as given. This isn't a problem intrinsically – puzzles of this type are fun. The problem is that some of the other puzzles are ambiguously written. When you've been trained to find loopholes in the problem text, and then the problem text starts having ambiguous segments in it . . . things get bad, quickly, and I failed several puzzles because I was thinking too carefully and not choosing the "obvious" correct answer. I wasn't having trouble solving puzzles. I was having trouble interpreting puzzles.

Worse, failing a puzzle gives you a permanent, irrevocable penalty. Each puzzle is worth a certain number of "Picarats", which they say is currency but which you could easily describe as "points". Answering a puzzle wrong reduces its worth by a certain amount – usually by 1/10 of its base value, but for multiple-choice puzzles it's often up to 1/4. There's no way to get these points back, besides starting the game over or saving before every single puzzle. You can replay puzzles as many times as you wish, but since they contain literally no random component, repeatedly solving them gives no extra bonus. (I eagerly await the first Professor Layton speedrun, as it will be moderately hilarious due to how predictable each puzzle is.)

What this means is that each time you interpret a puzzle incorrectly, due to ambiguous phrasing, the game penalizes you quite harshly. And, as someone who likes being able to perfect games, this is frustrating. The game does provide a hint system that you can check to get suggestions for puzzles (each hint costs a hint coin, which are available in limited quantity throughout the game, though profusely enough that I never felt worried about running out) but the hints are frequently either unhelpful or too blatant, and there's no way to know what sort of a hint it will be before purchasing it. In either case, they rarely cleared up the ambiguity without practically solving the puzzle for me. I'm not sure if there's a solution to all of this, besides semi-randomized puzzles and some ability to retry puzzles and reclaim your points, but it's probably the most irritating thing I ran into in the game.

There's little more to say about the puzzles – they're puzzles, they're (mostly) well-constructed and they seem to give the right number of points for their respective difficulties. Despite being the core of the game, it's oddly hard to talk about them, due to how diverse they are – any real in-depth discussion would be pages long, and I don't have that much to say. So I won't get into depth there – for the purposes of this dissection they're actually the least interesting part.

The Plotline

Back on a lighter note, though, the plot is almost perfectly suited for the game in more than one way. The plotline is, in many ways, a puzzle itself – you can go through the game without thinking about it if you wish, but I suspect most people who play the game treat the plotline itself as another optional puzzle, and it holds up quite well. Plot is delivered by people's discussions and by clues found in the village, and occasionally by Layton himself, who reveals villains in a manner Sherlock would indeed be proud of. (It's a little unclear where the player stands in all this, as the player is clearly not strictly either Layton or his protege Luke, but this never really gets in the way.) Most of the plot can be solved, by the player, before the denouement, and any fan of mystery novels knows that this is both crucial and surprisingly difficult.

Major spoilers begin here. Skip down to where I say they end (it's also in bold) if you don't want to read them.

Better yet, all of the major plot points are delivered very early on. The tower is clearly important, the highly-suspicious murder of one of the village inhabitants happens practically in scene 2, and every single suspicious point is laid out clearly near the very beginning of the game – and the vast majority of them are resolved, in rapid-fire, at the very end. The game pulls you in and doesn't let you go until the last threads are finished. In a brilliant stroke the developers included a section of the interface that lists the major unsolved mysteries, easily showing you everything that has not yet been answered.

I mentioned above how it felt like the entire village existed solely to give you puzzles, and as it turns out, that's exactly what the situation is. The village is a collection of puzzle-providing robots, built to test potential caretakers for the Baron's only daughter, Flora, who they have been taking care of for years. (Obviously anyone good at puzzles will be a proper caretaker. That's just how things work in Layton's world.) Besides Flora, the only human in the town is Bruno, the Baron's old mechanic and the designer and maintainer of the robots. Once Layton arrives, Bruno traps him there, along with Layton's archenemy Don Paolo who we end up knowing essentially nothing about, and that's why Layton is stuck in a town with a bunch of robots answering puzzles.

Clear?

Good.

The game ends up with "To Be Continued" and at least one giant mystery, namely who this Don Paolo person is and what he has to do with Layton. The game series is apparently designed as a trilogy (the second game in the series is now available in Japan and will doubtless be ported to English rapidly) and I presume its plot will be laid out in more detail in the future, but at the moment Don Paolo is a bizarrely loose thread in an otherwise extremely tight story. It almost feels like, at the last minute, they decided they needed a villain and so they grafted Don Paolo in. Similarly, Don Paolo's plotline really isn't a puzzle in any way. Don Paolo is masquerading as a detective, and very early on you think the detective is merely a jerk – there's no sign that he's a fake – but quickly it becomes clear that something is very wrong with his behavior, and the plot simply isn't subtle enough for him to be anything other than a villain. When he unmasks himself (thanks solely to Layton calling him out, and a small amount of evidence, most of which showed up after his villain status was clear to anyone who understands plot) it's just not a surprise, and it's far too late for you to feel clever for solving the puzzle quickly.

Why is he here? What's his connection to Layton, if any? We just don't know.

Major spoilers end here. Welcome back!

So in the end, the plot is good. Definitely good – we're well past the "there's a guy, and he's evil, so go kill him thanks" stage. But it's not perfect, and there are dangling bits that should not be dangling. I'll have to see if and how those are tied up in the sequels.

I'm running out of things to say, and I think it's time to finish this.

What Worked

I can't say enough good things about the atmosphere in this game. I think I may actually make tea for myself when I play the sequel, just to get more into the mood. The game is beautiful in a fashion which does not draw attention to itself – the art and town designs exist solely as a backdrop to the puzzles, and they support the puzzles magnificently.

What I'd Change

The weakest point is the puzzles – and that's really saying a lot, considering the quality of the puzzles. However, some of them are just a little too ambiguous and irritating to feel satisfying. I don't know if they got a serious game rules-lawyer type to go over the puzzle descriptions in agonizing detail or not, but if they didn't, they should have. Few things are more irritating than being seriously penalized for something that could have honestly been taken multiple ways. Just shouldn't happen.

The first thing I'd do is hire someone truly obsessive and anal to go over the puzzles and find every single point of ambiguity. As a programmer, I think a programmer would be perfect for this. Each of those points need to be squashed, and completely, unless it's actually the key to the puzzle. The only ambiguity left should be intentional ambiguity.

If I had more time, I'd figure out some way to partially randomize puzzles, and rig up a system where you could reclaim points by retrying puzzles. It should be possible to get a perfect score with sufficient skill, even after you've "beaten the game" with an imperfect score.

What I Learned

If you're building a game around a single concept, make sure the entire game revolves around that concept – the main gameplay, the supporting interface, and the plot. A game based around timetravel without an insane self-referential plot just isn't right, and if you're writing a game about puzzles, every part of the plotline should be a solvable puzzle. Layton got that about 90% right, which leaves the remaining 10% surprisingly glaring.

But honestly, I can't fault it too much, and I'm eagerly awaiting its sequel.

The Mario 64 series has a gameplay style which I honestly can't say I've seen in any other game ever. Your goal ("save the princess") is governed by a very simple game mechanic: a series of things you must collect. In Mario 64 it was stars. In Mario Galaxy, well, it's stars. In Mario Sunshine you had to defeat Shadow Marios, and the way you got to them was by collecting "shines" . . . which look exactly like stars.

The Mario 64 series has a gameplay style which I honestly can't say I've seen in any other game ever. Your goal ("save the princess") is governed by a very simple game mechanic: a series of things you must collect. In Mario 64 it was stars. In Mario Galaxy, well, it's stars. In Mario Sunshine you had to defeat Shadow Marios, and the way you got to them was by collecting "shines" . . . which look exactly like stars.

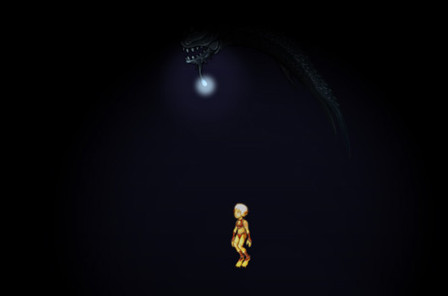

The Abyss is dark. There is no light. The only light in the level comes from you, in your Sun Form, which coincidentally means you can't attack. You're either reliant on Li for attacks or you're switching forms like a madman for any kind of combat. Or you simply run away from everything, which is what I did. Down down down in the bottom of the Abyss is a large door, marked with symbols that I recognized from Li's cave. I checked it out, ran into it a few times, tried playing Li's song, tried shooting it with fireballs, growing plants on it, and using all the forms I could to get it open. Nothing worked. Eventually I gave up and went looking for another area I hadn't yet explored.

The Abyss is dark. There is no light. The only light in the level comes from you, in your Sun Form, which coincidentally means you can't attack. You're either reliant on Li for attacks or you're switching forms like a madman for any kind of combat. Or you simply run away from everything, which is what I did. Down down down in the bottom of the Abyss is a large door, marked with symbols that I recognized from Li's cave. I checked it out, ran into it a few times, tried playing Li's song, tried shooting it with fireballs, growing plants on it, and using all the forms I could to get it open. Nothing worked. Eventually I gave up and went looking for another area I hadn't yet explored.