New Game+ and Free-to-Play: Making your biggest fans happy

2012, March 31st 12:35 AMThere's a phrase I've heard a lot lately. "Long tail". The theory is that there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people out there just waiting to give you small amounts of time . It's a good theory, and it's accurate, but there's a corollary to it: there's a small number of people out there just waiting to give you *huge* amounts of time.

As game developers, we, of course, want to harness that. Luckily, there are a few good ways to do so.

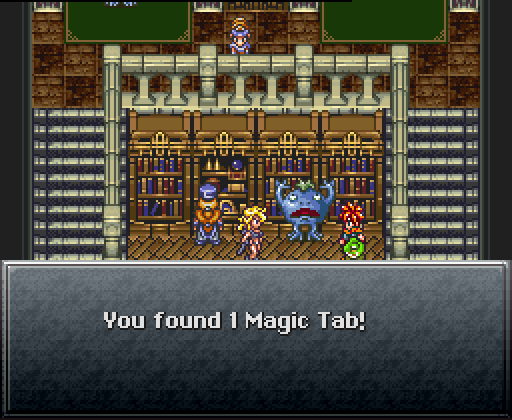

Many years ago, back in the SNES days, a game called Chrono Trigger had a clever innovation. You beat the game, and then, after the game was done, you could start the game again . . . with your existing characters, levels, and equipment, and with a whole pile of new endings unlocked. It was called New Game+.

The beauty of New Game+ is the the most devoted players, those who had loved the game and wanted to keep playing it, could keep playing it. It wasn't just a grind either, there were things to do that you could do only in this new mode. For example, killing the boss five minutes into the game, with a single character, resulting in a completely new ending. The game contained a lot of equipment that could be gotten once only, but of course, on the second playthrough you could get it again, allowing for combat strategies that simply weren't possible on a single playthrough. And, of course, you could see the effect of different choices on the plot, without having to spend all the time slowly bashing your way through the game at a normal level.

Most players, I assume, never tried New Game+. Or perhaps they tried it for a few minutes and stopped. But some – a very small number of players – played the game over again, once, twice, maybe more, trying to unlock all the endings and all the equipment, just enjoying their time in the game world that they loved.

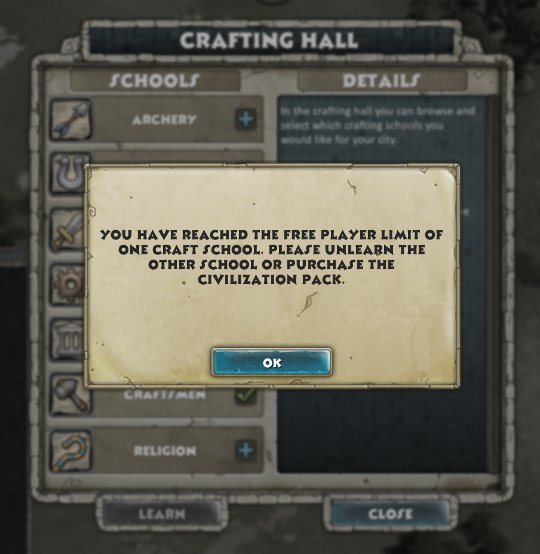

Recently, there's been an interesting new financial model for games. It's called Free-to-Play. The idea is that you provide a game that doesn't cost any money, then you ask people to start forking over cash once they're already playing. There's a bunch of variations – some leave you hilariously underpowered unless you're giving them money, some games make it mandatory to give them money to proceed, some games make it frustrating to not give them money, some just constantly hound you for money, and some provide a fun game and let you fork over cash for vanity items and out of laziness.

I think there are a lot of interesting moral comments you can make about the various first variations, but this entry isn't about that, which is why I'm going to talk about the last one. Tribes: Ascend is nearing its release date and it's one of the more elegant and friendly Free-to-Play models I've seen. The only things that require money (known in-game as Gold) are purely cosmetic skins – everything else can be acquired simply through experience, acquired by playing the game.

And we're not talking boring grinding, either. The game is a team-based competitive shooter. You get experience by playing the game in a normal fashion. Now, you might think this means that someone who finds the game fun wouldn't want to give them money – after all, there's no reason to do so, you can still unlock everything without it – but there are two distinct groups of people who happily pay out.

The first group is the obvious group: those with more money than time. The game's fun, they want to unlock classes and items, here you go, have some money.

The second group isn't as obvious. It's the group of players who absolutely love the game.

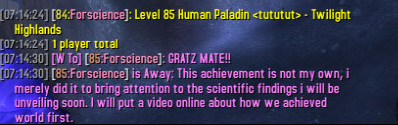

About two weeks ago the first player reached Rank 50. Ranks have absolutely no bearing on the gameplay, they're merely an indicator of how long you've been playing. He's been playing a lot. He posted a screenshot of his progress, and one of the things quickly noticed was that he had enough experience to unlock every single item in the game several times over, enough gold to unlock every single item in the game several more times over, and enough Boost – an experience-multiplier purchased with Gold – to easily acquire yet more complete experience-based unlocks. And it turns out that he'd recently paid them even more money.

There's no logical reason for him to do this. You literally can't unlock anything repeatedly. He already has enough experience and gold to most likely unlock everything the developers will ever release. And yet, he loves the game, so he's willing to put more time and more money into it.

The long tail is usually a major point of interest with free-to-play games. In theory, there are hundreds of thousands of people out there who don't care enough about your game to give you $10, but maybe you can get $2 out of them, or maybe you can get them hooked and get $5. And, yeah, you get a lot of money off those people. But nobody talks about the outliers – the people who give you $300 extra just because they really enjoy playing your game. The people who will finish your game from beginning to end two, three, five times, as long as there are things for them to work on and achieve.

I think there's a lot of crossover between the free-to-play customers and New Game+ players. In both cases, there's a person who has deeply loved your world and wants nothing more than an excuse to give you more money, to spend more time playing, to do something more in the world you've created. Not only is this person going to play more, but they're going to evangelize you to their friends.

That's valuable, whether it be in goodwill or cold hard cash.

If you're making a game with a world, if you're making a game with an experience and not just a final boss, remember to let the player leave your world at their own pace. If they want to stick around, make sure there are things for your player to do. The benefits are hard to calculate, but you'll find them very valuable.