Embracing Unintended Game Design

2011, July 29th 9:51 AMI've done a lot of pen-and-paper roleplaying over the years.

I started with Dungeons and Dragons Second Edition, or, more exactly, I started with a horrifyingly botched interpretation of the rules, filtered through my middle-schooler mind. I vaguely recall rolling a d20 for stats and I'm pretty sure we had no idea what spell slots were. Since then I've played three major editions of D&D, three major editions of Shadowrun, had a brief and unfortunate foray into the world of Rifts and a briefer and far more unfortunate foray into a hand-rolled Xanth roleplaying system, and, to be quite honest, spent far more time thinking about roleplaying than I actually did roleplaying.

Anyone who's hung around roleplayers has heard a bunch of the same horror stories. I played this game, the whole damn thing was on rails, we had to read the GM's mind. The GM was a control freak and everything had to happen his way. It was a great game, except that the story always followed the GM's plan, no matter what. If you've played games, you know this GM. You've probably met him, you've probably played in his games, you've probably spent a frustrating hour coming up with clever plans and having them shot down unilaterally.

I used to be that GM. I'll admit it. My Xanth games were the worst example – little more than a thinly veiled excuse for running through the plot of the books, including skipping entire chapters when I couldn't figure out how to shoehorn the player through the *cough* scintillating plotline. My Rifts game was better, albeit only slightly. I had one of my best moments in that game, when the players managed to spy on the enemy encampment and, as what was intended to be a throwaway bit of scenery, I mentioned a huge dragon sleeping off in the corner of the camp. This kicked off about four hours of violent explosive shenanigans that left the camp in ruins. Followed immediately by one of my worst moments when I Deus Ex Machina'ed the entire thing away so I could give a speech. Seriously, Zorba. What the hell were you thinking.

The nice thing about RPGs is that the GM is sitting there, and the GM is a human. So when the players say "fuck that, we're not going into that cave to rescue the Mayor's daughter, that's way too dangerous" the GM can come up with a solution. Maybe they get driven inside. Maybe the mayor offers a bigger reward. Or maybe they just walk away and in the next town they have to deal with people telling stories about the adventurers that ran from a fight. You can improvise, and a good GM will improvise.

You can't really do that with games. When you release a game, that's the game, that's what the player's going to play. If the player doesn't want to go into that cave, well, tough cookies, the plot isn't going to continue until you do.

And that's not really a bad thing. We've only got so much money we can pour into game development. We can't make a game where the player can go into the cave and kill goblins, or the player can go abandon his adventuring lifestyle and become a farmer, or the player can hire mercenaries to go in and clean out the cave and then turn the cave structure into an amusement park serving Goblinburgers and Gnollshakes. We can't make all that stuff fun, we just don't have the developer time. And, for many years, that's where the limit was: you implement a game, the user plays the game, the user beats the game, hooray.

Then we invented multiplayer games and all hell broke loose.

It turns out that human social structures are unbelievably complicated. It turns out that human motivations are deep and multilayered. It turns out that when you have the goal "kill a bunch of monsters, you are a better player if you kill more monsters", and you expect people to go kill monsters independently, some bright person is going to realize that, hey, you can pay people to help him kill monsters, and then he's a better player because he's killing more monsters!

The industry response to this is swift and predictable: They're playing the game wrong. Put them back in their box and tell them to play the game right this time.

And it doesn't work, because we seal up one exit to the box, and then it turns out there's another exit, and the whole thing happens again.

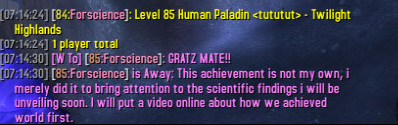

When World of Warcraft: Wrath of the Lich King was released, a player named Athene had a clever strategy to reach level 80 before anyone else. Despite asking the GMs for permission, he got banned for it because he wasn't playing the game right. When World of Warcraft: Cataclysm was released, he tried again, this time succeeding. Wanna guess what will happen when they raise the cap to 90? I'm willing to bet Athene will be there powerleveling to 90.

When someone finds a hole in the rules, our first reaction as game developers isn't "whoa, awesome, they found a new way to play!", it's "We have to stop them, because this is our game and you're not allowed to do that." Which we can do, because it's our world they're playing in, we can just push a button and make them stop doing whatever they're doing. Back on the beaten path, boy. That's where you're meant to be. And the game goes on, and we rest, satisfied that we're the master of our own domain, and that the players are playing the game correctly.

Which goes all to hell when we do something outside our domain.

Example One: Chain World. Jason Rohrer bought a Flash drive and put a copy of Minecraft on it. He gave it to someone, with a single set of rules: Do not copy it. Play the game once, building and creating whatever you wish. When your character dies, pass it on to someone else. These are the rules and these are the only rules.

The rules were broken instantly. Jia Ji was the first person who got it, and he put it on eBay and made the buyer promise to send it to specific people next. The community was outraged. He's playing the game wrong. Then broken again, perhaps – the game may have been destroyed, the game may have moved on, but nobody's saying. The rules lasted exactly as long as it took Jason Rohrer to describe them.

Example Two: Eric Zimmerman's coins. At the most recent GDC, there was a talk, and during that talk, coins were handed out. At the end of the talk, the person with the most coins got to give their own talk. Those were the rules, and the rules were defined by Eric Zimmerman.

Ryan Creighton used social engineering to acquire the entire bag of coins, and the watchers were outraged. He's playing the game wrong. So Eric broke his own rules, and gave the extra talk to someone he felt was more deserving. Then Eric broke his own rules again, and let Ryan talk for ten words. Ryan, of course, broke that rule, and gave a substantially longer talk than ten words.

You make a game. You offer to let someone play the game. They play a different game than you intended. Then you get angry that they're playing the wrong game.

This is a mistake.

When Athene plays World of Warcraft, he's not playing Blizzard's World of Warcraft. He's playing Athene's World of Warcraft. It's a similar game, with some of the same fundamental rules, but with different guidelines. In Blizzard's World of Warcraft, you don't join and drop groups to maximize the amount of experience you gain. In Athene's World of Warcraft, you do. And, critically, these are the same games. Neither game has a rule that says you cannot, or that you must, but in Athene's game, which Athene plays to accomplish Athene's goals, you do.

Jason Rohrer bought a Flash drive to make Jason Rohrer's Chain World. Then he gave it to Jia Ji and Jia Ji turned it into Jia Ji's Chain World. Jason Rohrer invented Jason Rohrer's rules, and Jia Ji invented Jia Ji's rules.

Eric Zimmerman invented a game involving coins, and he made Eric Zimmerman's Coin Game. Then he gave it to a room full of people, and each person invented their own coin game. Many of these were equivalent to Eric Zimmerman's game, but Ryan Creighton's Coin Game was different. You see, Eric Zimmerman's coin game was about collecting coins, and Ryan Creighton's coin game was about collecting coins in a slightly different manner that Eric Zimmerman hadn't thought of.

Jia Ji wasn't following Jason Rohrer's rules, and Ryan Creighton wasn't following Eric Zimmerman's rules. But Jason and Eric had let their games escape, and someone else had found a new way to play it. When they realized that, they tried to bring the game back. No. That's my game. You can't play it like that. You're not playing the game right.

But it wasn't Jason Rohrer's game anymore, and it wasn't Eric Zimmerman's game anymore.

When we make a game, we give it life. We create the rules of its existence. But then we send it out into the world, and other people take the game and change the rules and make it their game. Traditionally, this happened in people's homes, with house rules and tweaks and simple unintended misunderstandings, with people finding a new way to play the game or inventing a strategy that we never considered. But today we make huge multiplayer games. When we let the game go out, we tell people they're allowed to play it, but then we punish them for not following our view of how it should be played. We're telling them to play, then forcing them to follow.

I think this is a mistake. More accurately: I think reflexively doing this is a mistake. With multiplayer games there are certainly situations where someone finds it fun to destroy other people's enjoyment of the game, and that should be taken care of, ideally swiftly. But in a situation where one person has invented a new way to play the game that does not harm others, what's the issue? In a singleplayer game, or a sandbox game, or even a multiplayer game, why, whenever we are confronted with someone who's playing our game in a different manner, is our first instinct to stop them?

We cannot and should not hover over people's shoulders, telling them how to play the game. We should develop games that people want to play, and if they discover a way to play the game that we were not aware of? Maybe that's for the best. Maybe we can learn from that. Maybe we can say, hey, you are not playing the game I invented, but that's cool, and your game looks like fun, how about if I change my game to behave more like your game.

Maybe we need to learn to let go of our toys and let others play with them for a while.

Maybe we'll learn about some new games.

Casper

2011, July 29th 1:28 PMHi there! Interesting read..

I think the problem that designers have when they see someone playing the game "the wrong way" is that it more often than not destroys the other players' fun.

In the example of Athene, he discovered a 'dominant strategy', which could make other players enjoy the game less, in the sense that they would think "hey, he's cheating! that's not fair!" If the only way for those people to be as 'good' (i.e. level-up as quickly as him) as Athene (which is for most players the goal, I would suppose) is to also use Athene's way of playing the game, which might not be the most 'fun' way to play the game.

The same is true for Ryan Creighton's hustle. I don't think it was just Eric Zimmerman who was bummed that Ryan had played the game that way, I think a lot of the other players might have felt bummed as well. In that sense, Ryan detroyed the other people's enjoyment of the game.

So, yeah, I'm all for letting players discover their own fun in games (I myself enjoyed hours of doing weird grenade-tricks in Halo),

but the examples you mention seem to fall under the category of destroying other players' fun, so I guess it'll be really difficult for designers/GM's to decide when to intervene and when not to.

Zorba

2011, July 29th 5:14 PMWhile I agree that destroying the other players' fun is a problem, I don't think solving it is as simple as you're thinking. If it wasn't Athene, it would be someone else with a slightly less clever degenerate strategy. If you got rid of everyone with degenerate strategies, it'd be someone without a job who's willing to forego sleep. It doesn't matter how many people you ban from the game, people will still be complaining that it's unfair because they had a clever strategy/had friends/played Shaman/were on a server with fewer people/were on a server with more people/etc etc etc. Athene's just noticed because he's the #1 person, but get rid of him and you have a new #1 person.

There's a same situation with the Creighton situation. In the post I linked to:

It wasn't fair from the very beginning, Jane McGonigal was practically a sure thing. Eric Zimmerman's game was a social manipulation contest, but Jane McGonigal's game was a popularity contest, and that's a game she was sure to win. Why is Ryan's game any less valid than Jane's game, considering that they're both exploiting things outside the rules in order to win?

I think in both these cases, the fun was destroyed long before Athene or Ryan got there. Athene and Ryan just came up with a way to do it more efficiently, and the people who weren't quite as efficient resorted to complaining about fairness.

nightraven

2011, July 30th 4:39 AMHello there!

A really interesting approach to explaining how unintended game design should be handled.

However, I have a question ever since I read the example involving Athene's World of Warcraft.

If he is playing his own different game, should he not play it elsewhere, along with others that also play his game rather than Blizzard's? I know… it's kind of strange to imagine it with this example. After all, he is still playing Blizzard's WoW in a 90%+ percentage.

What I actually wanted to ask was: In multiplayer, where different users COULD play the game in a different way than that which was intended by the designer, SHOULD they play all together?

Zorba

2011, July 30th 6:16 AMI think that's a really good question that I don't have a good answer for.

The great strength of MMOs is the network effects. I might enjoy playing the game for the lore, and you might enjoy leveling quickly, and my friend might enjoy acquiring gear, and your friend might enjoy taking on challenges, and our mutual friend might enjoy achievements. We get everyone together and we've got a dungeon team. We're all getting what we want out of it, and we're helping each other do it – with the terminology I have in the above post, we're all playing different games, but somehow, we're also simultaneously helping each other in our own games.

The great weakness is, of course, those very same network effects. If I can't find other players to do this stuff, I quit the game, thereby making it less likely that other players will be able to find me to do things. When MMOs collapse they tend to do so quickly and violently.

So, this is sort of a copout answer, but my first answer is that this partially comes down to things we don't know the answer to, and partially comes down to the definition of "should". Would users be happier if everyone they played with was likeminded? Yeah, probably. Would users be less happy if they couldn't find anyone to play with? Yeah, probably. Would users be less likely to discover new parts of the game if they were on a server with only similar players? Almost certainly. Would that lead to less satisfied users? Probably. Since splitting users into different game groups would accomplish all of those, I really couldn't say whether it would make the game more fun overall, and I certainly couldn't say whether it would result in longer-lasting subscriptions or more money intake for the game developer. And I also couldn't say which of those is important. But I do feel like one of the important parts of an MMO is the Massively Multiplayer part, and if we did start moving players off onto their own servers, we'd be sacrificing a large part of that . . . which, in the case of MMOs, seems dangerous.

So there's a giant non-answer for you. :)

But as for another answer, I'm not sure it matters. Athene only plays on one server. In all meaningful senses, he's not playing "with" the vast majority of World of Warcraft. And yet, somehow, what he does on his server is still interesting to people on other servers. If we shuffled Athene and all the powergamers off to a separate server, it wouldn't really matter, you'd still have people grumbling that Athene was using trickery to become "first" even though they will literally never interact with him.

And as the converse of that, even if you're standing next to someone ingame, you're not necessarily playing "with" them. When I'm questing in an MMO I'm basically playing solo. Sure, someone could come along and kill some monsters, but MMO monster spawns tend to be tuned so that several players can do a quest simultaneously without issues. It doesn't matter if the guy next to me is a powergamer or a lore addict or a casual player or Athene, I'm neither going to know nor care.

The middle ground is the iffy bit – the points where one player's behavior really does influence other players, but only the other players near them. PvP zones, griefing, dungeons, that sort of thing. And as for that, I honestly don't have a good answer, that's where the above non-answer comes in.

And as a *final* answer, I think it would be extremely difficult to figure out which lines to split games along. I mean, I'm a casual but determined raider who enjoys lore and achievements, isn't interested in roleplaying, and has an inconsistent schedule. Which game am I playing? Well, I'm playing my game, but relatively few people out there are playing my exact game. Who do I get lumped in with – the hardcore raiders? The casual raiders? The loremasters? The achievement-seekers? I wouldn't be satisfied in any of those groups.

Wow this ended up longer than I was expecting.

EricM

2011, July 30th 12:16 PMAny discussion of unintended game design outcomes is incomplete without mentioning the Tribes series, or at the very least it is the best example I can think of. The core feature of the games, that of skiing (frictionless sliding over hills combined with jetpack use to gain enormous speed), was originally a bug in the beta of Tribes 1. The designers (notably Scott Youngblood, currently working on Firefall with Red 5), instead of patching it out, embraced it and spawned an entire series of games.

There are certainly instances where players find unintended ways of doing things that should be removed/limited, no question about that. The metric for determining the response should be based on overall player and playerbase fun related to the trick/method. Methods of griefing/teamkilling are fun to a few players, but enormously un-fun to their victims, so of course they get patched out. An example of a slightly more 'gray' are would be in early Battlefield 2, where Recon players with C4 were able to throw C4 in a certain way that made it fly forward for about twice its normal throw distance. They could then detonate it mid-air and easily get kills. While many of the competitive players were enjoying it, the anti-fun it caused for the newer/lesser skilled players simply outweighed the benefits it was giving to those who used this method, and there was little visual feedback as per just how they were dying so easily. As such, it was eventually patched out.

Stiltskin

2011, July 31st 7:45 PMThis doesn't just happen in multiplayer games. It's a problem with modern gaming in general. Consider this:

"We can't make a game where the player can go into the cave and kill goblins, or the player can go abandon his adventuring lifestyle and become a farmer, or the player can hire mercenaries to go in and clean out the cave and then turn the cave structure into an amusement park serving Goblinburgers and Gnollshakes."

This seems like a perfectly good argument when considering modern games. After all, the game has to progress *somehow* right?

But then you consider a game like Minecraft. You can clear out that cave, weaving your way around creepers and zombies. Or you can ignore adventuring entirely and build a farm. And in multiplayer you can even bribe some of your friends to clear it out for you so you can turn it into an amusement park. And that's its biggest strength.

I've been playing Final Fantasy 3 DS lately, a remake of one of the old-school NES Final Fantasy games. I recently unlocked a ton of cool new jobs for my characters — Summoner, Black Belt, Devout, Ninja, and more. I decided to switch all my characters to these new jobs, which requires a bit of grinding to get them back to a good level of usefulness. I also chose to explore new areas and go into a couple of side dungeons to obtain some new summoning spells. But the important thing is that these were my choices. I could easily have chosen to keep my old jobs and ran straight into the final dungeon. After all, I had a pretty damn good White Mage and Monk, both highly skilled in their jobs. But I chose to take some time to play around with the new jobs.

Or consider Pokémon. Do you catch every new Pokémon you see? Or do you rush through with a small collection, adding to it only when you see something cool? Do you keep a core team of six from the beginning of the game, or do you replace them frequently to take advantage of type advantages throughout the game? Do you keep your team trained evenly, or do you keep one guy ridiculously highly levelled so he can sweep everyone? Do you tackle the grass Gym Leader with your current team or do you run out to grab a fire type that has a type advantage?

Even in a game traditionally considered "linear", like Super Mario Bros.: Do you run through the level at top speeds? Do use your spare raccoon suit and fly over most of it? Do you hit every block you see or duck on every pipe, to try and find secret areas and powerups?

Is Gordon Freeman a cautious person, who hangs back and hits enemies from a distance? Does he use his environment to his advantage with the Gravity Gun? Or is he a berserk, Rambo type who runs in madly, guns blazing? Does he carefully listen to what NPCs are telling him or does he fidget around impatiently, smacking things with his crowbar?

Contrast this with a game like Bioshock. It was praised, at the time, for giving you full control during cutscenes. Except what wasn't mentioned was that these cutscenes, despite leaving you full control of your character, were generally behind unbreakable glass barriers. You had no control over what happened. And you were led by the nose throughout the entire game. This ties in with the plot at one point, of course, but even after that "critical" moment, you were still led by the nose, and through stupider and stupider decisions. It's one of the big reasons I consider Bioshock to be a weak game overall.

What I'm trying to get at is that what you're describing — people playing their own games, rather than the ones the developer wants them to — happens in *every* game. And the best games are the ones who take this into account, and give you the freedom to play the game your way. In short, the player is much, much more important than the developer's "vision". And the sooner game developers realize this, the sooner games will return to a golden age.

(Also, as a side note, I've met Ryan Creighton before. He's a friend of a friend of mine. He's a pretty cool guy.)

Zorba

2011, July 31st 11:50 PMStiltskin, I started writing a response to that, but it basically comes down to "I agree".

Now, some of these situations are easier for game developers to deal with because they don't result in the gamer doing "better than intended". Gordon Freeman has a few major strategies to use, and those tend to run the gamut from "roughly as powerful as intended" to "actually, this is kind of a crappy strategy". But I'd be willing to bet that at some point in HL2 development, they found something that was "too powerful". Probably based around the Gravity Gun, because that seems like the sort of item that would result in unexpected strategies :)

I don't remember where I read this, but I vaguely recall that the original Gravity Gun was capable of picking up enemies and throwing them around. Now, one, how cool is that? It is really cool! But it turned out it was also massively overpowered. Valve is smart, so they took out that feature, but then reintroduced it later on in a spot where it could be balanced. So that's kind of the ideal – see a broken but fun strategy, figure out a way to make it work properly. Restricting it to a subset of the game is definitely one way to accomplish this.