The Ultimate Race Postmortem

2010, August 10th 5:23 PMSo, I made this game. And – let's be fair – it sort of sucked.

I could go on at great length about how this is Box2D's fault, and thanks to issues integrating Box2D with Lua. There's some truth to that. There's still bugs in there causing the physics to behave a bit wonkily. I spent a lot more time working on infrastructure and bindings than I'd meant to, and even today it doesn't work properly on Linux (and probably won't, to be honest, it's not a good enough game for me to spend the time on it.)

But that's not why the game isn't fun.

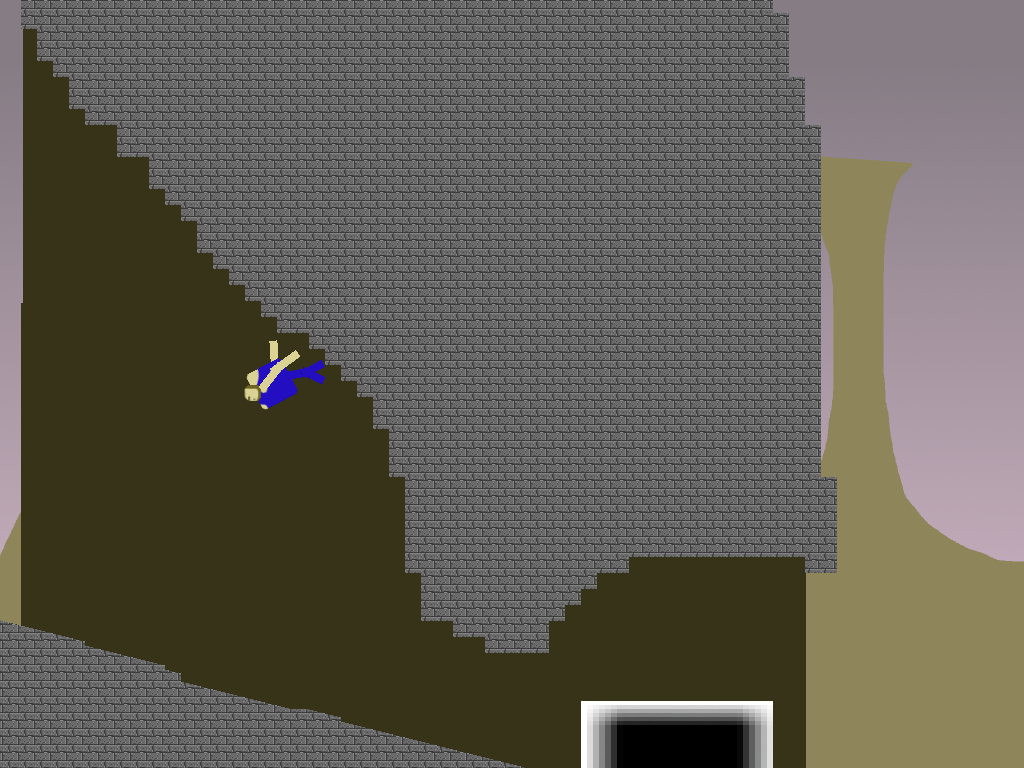

The original view I had of the game was that you'd be running along towards the next checkpoint, trying desperately to get there in time, and at the last minute you'd fling yourself towards the goal, die in midair, and get to watch your corpse crunching its way down the mountain until you happened to fall into the rejuvenator and oh god time to keep running go go go get to the next checkpoint.

But there's a bunch of problems here. First off, it requires you to make a crucial decision – your exact death position and velocity – before you can even see what you're trying to aim for. Second, physics tends to be extremely chaotic, so either the game needs to be built to funnel the player inevitably down into the right location or the player's death is near-certain, regardless of skill. And, of course, if you funnel the player down to the right location, then you're making skill irrelevant anyway. A game with no skill component tends to not be a good game, and as much as I rail against them for being low-skill, even Bejeweled and Peggle involve more skill than my original vision of The Ultimate Race did.

Even that isn't the crucial problem.

The reason the game isn't fun – and this took me a while to hunt down – is that a game of this sort is only fun if you're almost losing. If you get to the goal quickly, it's easy, and you'll never bother with an early death and it's boring. If you're nowhere near the goal, you lose no matter what and it's simultaneously boring and frustrating. The player has to be right on that knife edge of losing for that fun moment I had in mind to actually occur.

And that's just ridiculously hard to orchestrate.

If I were going to do this again, I'd be trying one of two different approaches. One is to make the difficulty self-balancing in a sense. I hate auto-adjusting difficulty, so in reality what this would mean is that reaching a goal very quickly would unlock a "harder path" that the player could choose to go on, so the player could make the game as hard as they could handle and thereby keep it fun.

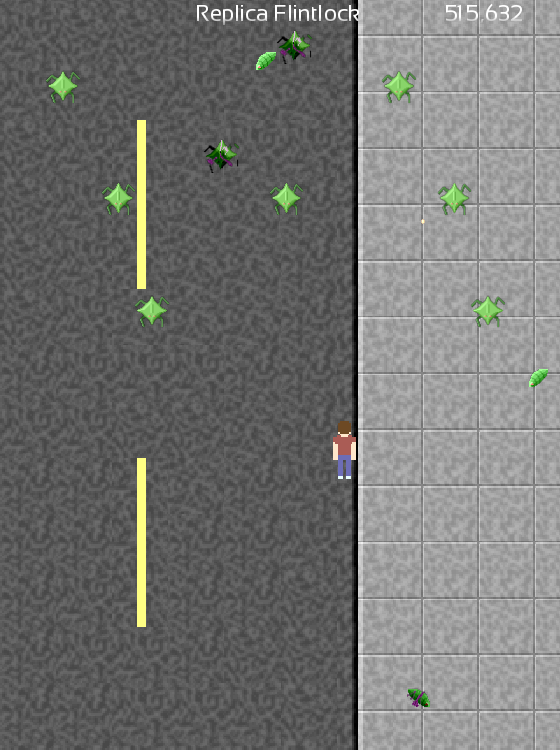

Another thing I would try would be to remove the time limit entirely, and even remove the voluntary-death button. I'd add some kind of a laser defense grid around the checkpoint. You die because you leap headlong into a laser and get fried, and that is when the whole "fall down the cliff praying" thing would kick in. I'd play up the "race" thing more heavily – you'd ideally be racing against a bunch of computer opponents that don't get shot by lasers ("sorry man, we're out of the reflective armor. good luck!") and so you'd be encouraged to leap headlong into danger without really spending a lot of time preparing.

And finally, the player needs at least some influence over the corpse behavior once he's dead. Even if that's limited to twitching in one direction or another. Something.

I feel like, in some sense, this game is a milestone for me. It's the first time I came up with an idea that just flat-out didn't work – the rest of my unsuccessful games have been unsuccessful because I didn't have an idea. So, I mean, I had an idea, and it sucked. That's progress.

I think that's progress.