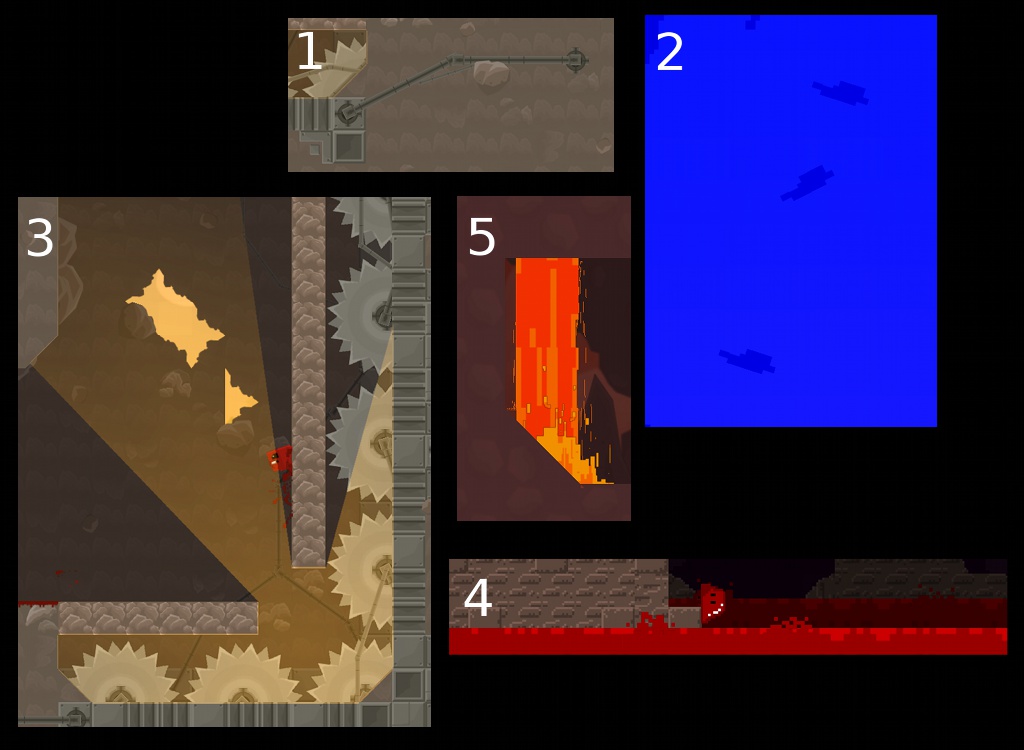

I just spent a lot of paragraphs talking about Super Meat Boy's artistic choices. Mostly, I talked about what made it a good facsimile of a classic console game while still, in a technical sense, being completely unlike a classic console game.

I didn't talk about what made it good. More importantly, I didn't talk about what "good" means.

From a big-business point of view, "good" is what sells games. That's cool. It's a rational choice. But it's not my choice.

From my point of view, "good" is what makes for good games. And by "good games", I mean "games that people enjoy, and games that people will continue to play well after release". The gaming landscape is littered with games that made a splash, but a stifled one – games that sunk unnoticed after their initial burst of sales. The indie market can't afford to do this. Indie marketing is a slow, gradual beast, and indie developers live or die on their long tail of sales.

That means when you're releasing an indie game, you have to release something that will still be fun a year from now. Two years from now. Five years from now. I can guarantee people will still be buying Braid in five years. I can guarantee people will still be buying Super Meat Boy in five years. And the way you get people to do that – at least, in terms of art – is to make art that lasts.

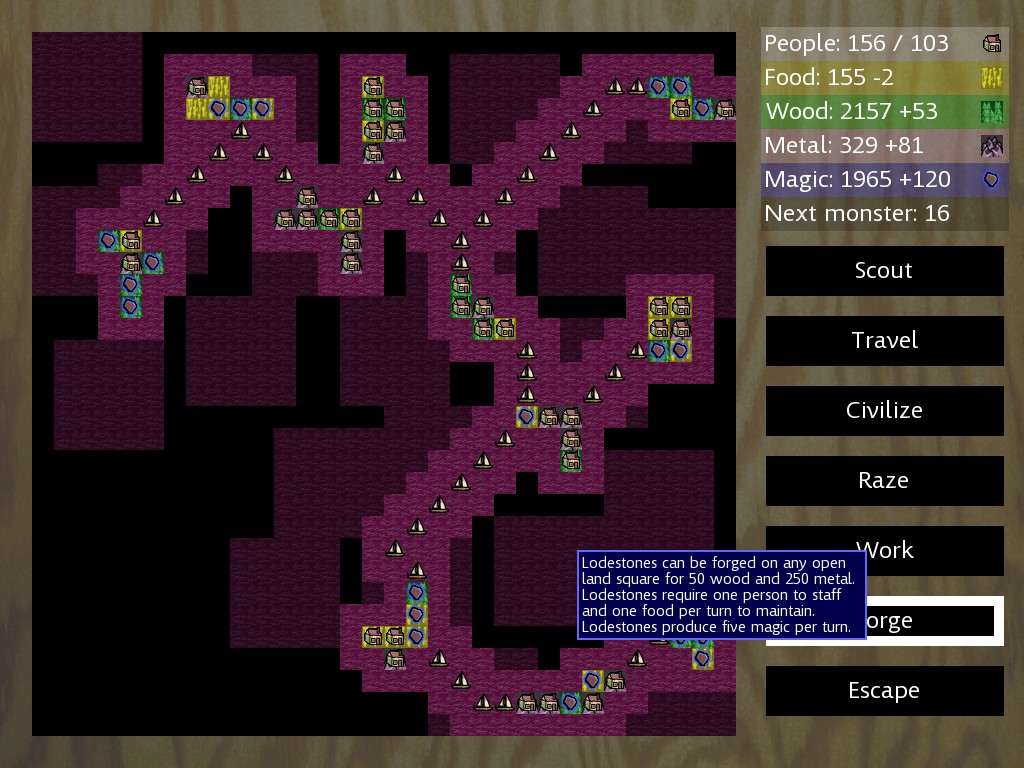

X-COM UFO Defense. This game's almost old enough to vote – seventeen years and counting. The graphics, by modern standards, are best described as chunky – this was back in the days when we were oh so excited about being able to display 256 colors on a screen at the same time, please ignore that we were restricted to a 320×200 resolution. But despite the chunkiness, they're good. You can see what's going on, the art doesn't induce pain, you get a sense of the world's style. The graphics may be old, but they're competently done and pleasant to look at.

Hold on to your hats, because we've got a shitload of screenshots coming up, all from around the same time period.

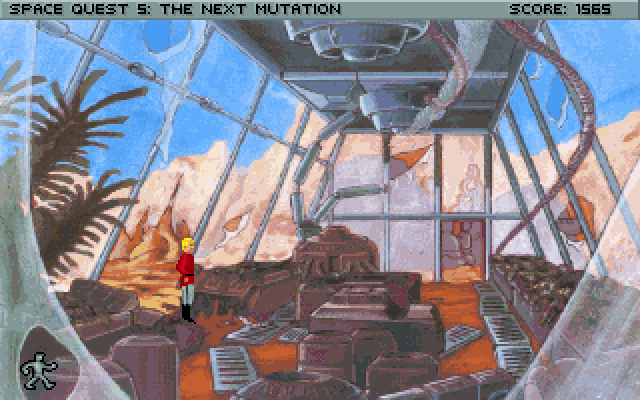

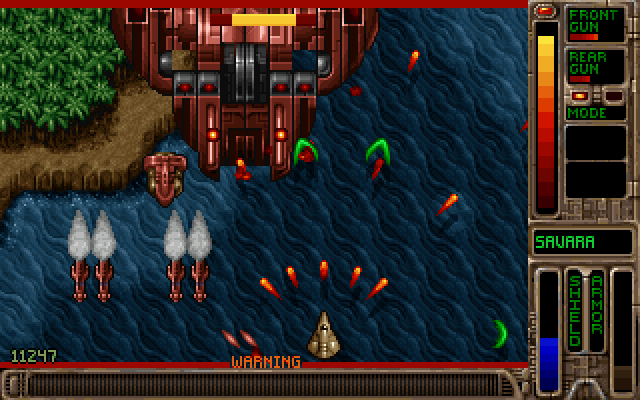

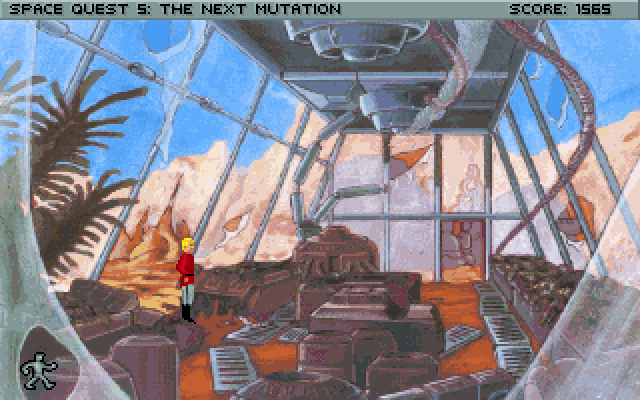

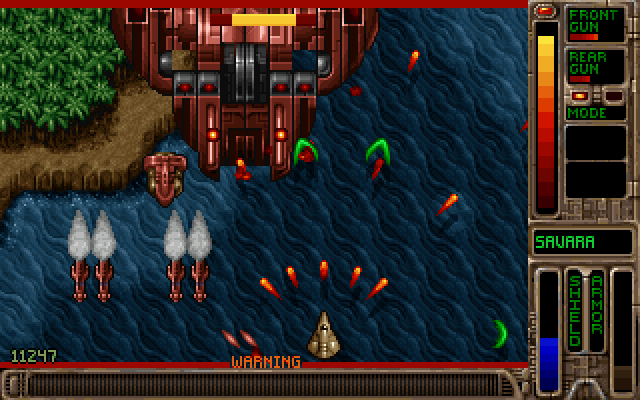

Space Quest 5 was one of the best adventure games of its time. Lavish hand-painted images, gorgeous worlds. Tyrian: a vertical shooter from Epic Megagames. It shipped with half a dozen detail levels, the highest of which would slow even the best computers down to a crawl. Jazz Jackrabbit was a successful attempt to bring the platformer genre over to the PC, merging the speed of Sonic the Hedgehog with the firepower of Doom. Master Of Orion 2 is an old 2d turn-based strategy game, setting you in command of an alien race to conquer the galaxy.

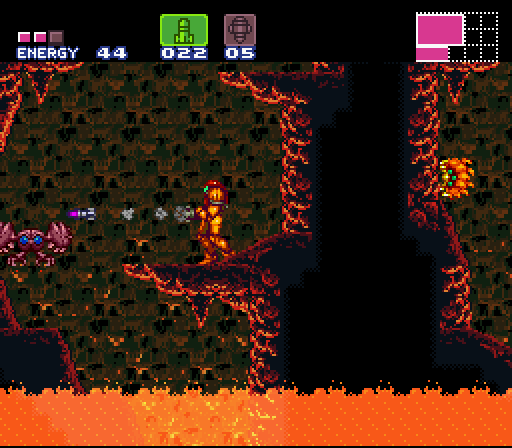

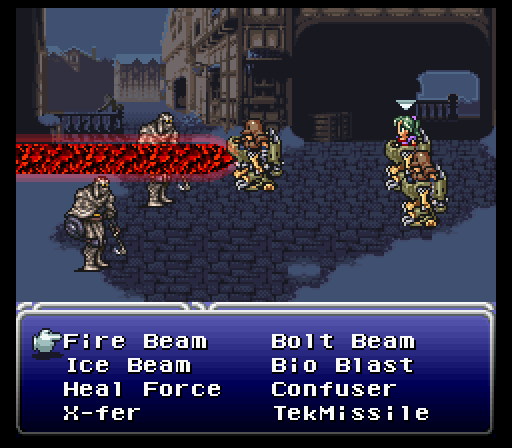

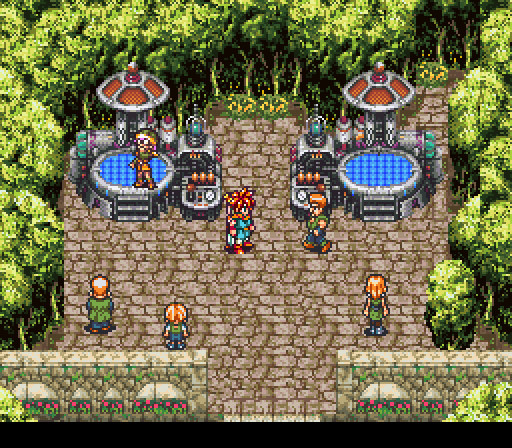

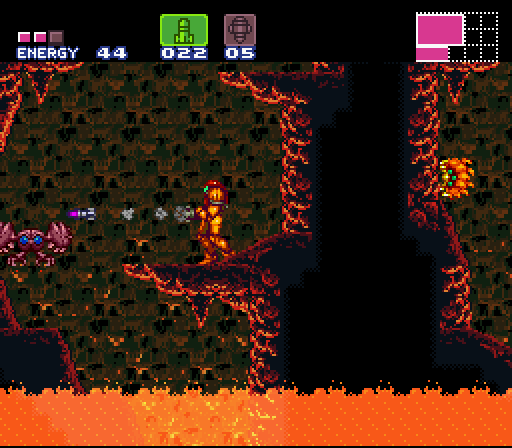

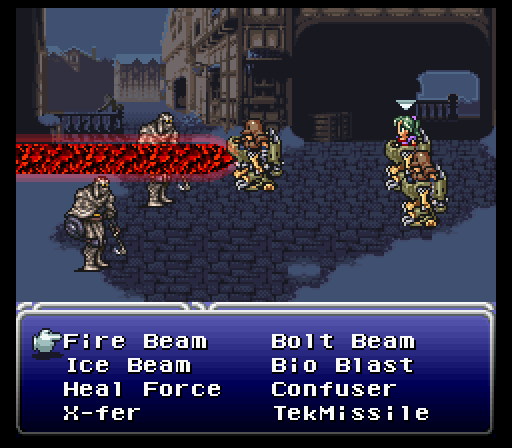

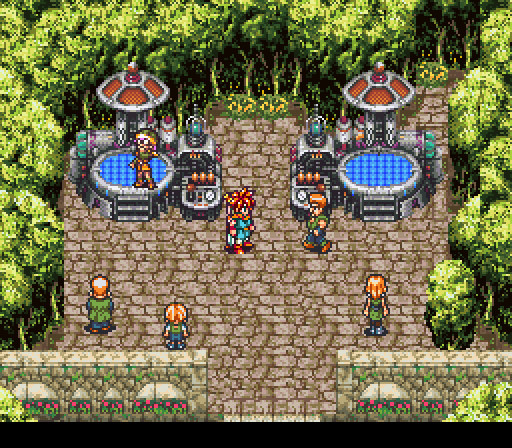

The PC wasn't the only platform with good, solid artwork. The Super Nintendo had its share as well. SNES cartridges were capable of storing up to four megabytes of data (six megabytes, if you pushed real hard) and their developers used this to its full extent. Super Metroid: still possibly the best game in its genre, it provided a gorgeous view into a strange alien planet. Chrono Trigger, a classic RPG, showed us the kind of variety an RPG could give us in graphics. I won't give away the plot twist in Final Fantasy 6, but suffice to say it was fantastically done, and – while it wasn't an SNES game – any discussion of gorgeous pixel art would be incomplete without Metal Slug. Which, if you can believe it, looks substantially better in motion.

All of these games have good graphics. I'm not saying they had good graphics for their time. I'm saying, even today, you can imagine sitting down and playing them. They look better than most modern Flash games.

(And you should play them, by the way. They're all really good. I'm not picking bad games here.)

And some games did not fare as well.

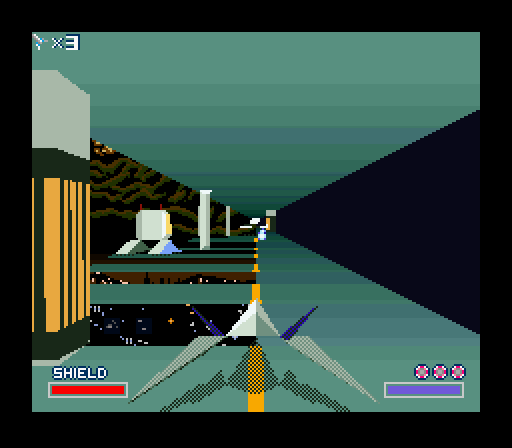

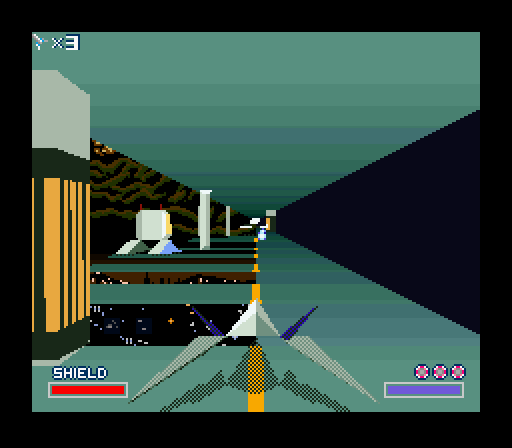

Alone In The Dark: A game that practically created the survival horror game genre. Final Fantasy 7: One of the most beloved RPGs of all time, even more so than Final Fantasy 6. Half-Life: The game that started a modern development behemoth, and one of the highest-rated games ever. Marathon: A relatively unknown first-person shooter that later spawned a somewhat better-known series called Halo. Starfox: The first 3d game on the Super Nintendo, creating an entire still-popular franchise of its own and firmly pushing consoles into the 3d world. And finally, Doom, which may well be the single most influential video game in history.

These are all considered great games. Some of them – perhaps even most of them – were even more groundbreaking and amazing than the games I've listed before. Most of them were released around the same time or later – the 2d games max out at 1995, the 3d games go all the way up to 1999.

But look at them. Seriously. They look like crap. The textures are low-resolution, either chunky or blurry. The models are blocky in the best of cases, and downright polygonal in the worst . . . and that's for the games that weren't using flat resized sprites. It feels like sacrilege saying that Doom is a game that looks bad, but, let's face it, by modern standards, X-COM looks good and Doom looks bad, even though fifteen years ago Doom is the game we were raving about.

All these games were released at roughly the same time, from 1993 for Alone In The Dark to 1998 for Half-Life. The earlier 2d games date 1995 or earlier. But all the 3d games look terrible, and all the 2d games look great. So what gives?

I didn't pick this time period arbitrarily. The mid-90's were the birth of the 3d gaming movement. Before that, we just didn't have the CPU horsepower to do 3d in any useful manner (yes yes, 3d Monster Maze and Catacomb, but I'm not even going to bother posting those). The instant we got 3d capabilities, people started making 3d games. They were new. They were amazing. And we simply didn't have the technology to make them look good.

Today, of course, 3d games are absolutely gorgeous. Photorealistic. Better than photorealistic, in fact. This is a line we've only reached recently, in the last few years. Logically, if we've only reached photorealism recently, that implies that 3d games have only just started looking good, yes?

And if you look back just a little, you'll find evidence corroborating this. Halo looked great on release, questionable now. Unreal Tournament 2004 is still a truly enjoyable shooter, but it's quite clearly dated. Serious Sam didn't look all that impressive when it was released, and it certainly hasn't improved. And Doom 3, hailed as a revolutionary graphics advance, is showing its age – blocky, not particularly atmospheric, and old looking. Better than Doom 2. Nowhere near Crysis 2.

And that means that no 3d game, before the present day, will stand up graphically. Right?

Well . . . no.

Not at all, actually.

Okami was released in 2006, but don't let the date fool you – it was one of the last games released on the rapidly aging Playstation 2, well after the release of the XBox 360. Its graphics come not from heavy hardware use, nor from a huge investment of money, but from style. Okami is a beautiful game.

Okami is not unique.

ICO and Shadow of the Colossus, two gorgeous games by the same developers. Shadow of the Colossus is a 2005 release, around the time of Quake 4. Ico was a 2001 release, back in the days of Halo. You can certainly see the lack of good technical backing to Ico, but it doesn't matter. The atmosphere of the game is clear, and the gorgeous art stands out today.

All of these games share something. They share a coherent visual style, one that could be accomplished with the technology of the day. And I do mean accomplished, not approximated. If you made Okami today, it would still look like Okami. If you made ICO today, it would still look like ICO. But if you made Half-Life today, it would look like . . . well, it would look like Half-Life 2 Episode 3. Not like Half-Life.

Today, hardware is no longer the issue. We have the hardware to do amazing things, as the above screenshot of Crysis 2 demonstrates. The issue today is money, and this is something that indie developers need to deal with regularly.

The genius of Super Meat Boy's art isn't just that the art is good. It's that the art is inexpensive. I have a hard time imagining that the game cost vastly more than Braid, and Jonathan Blow has estimated that Braid cost $200,000. The credits of Halo indicates that there were at least fifty full-time employees involved there, possibly more, and even calculating it conservatively, $200,000 isn't enough for half a month's salary for that many people.

Today, Halo doesn't look good, and Super Meat Boy does.

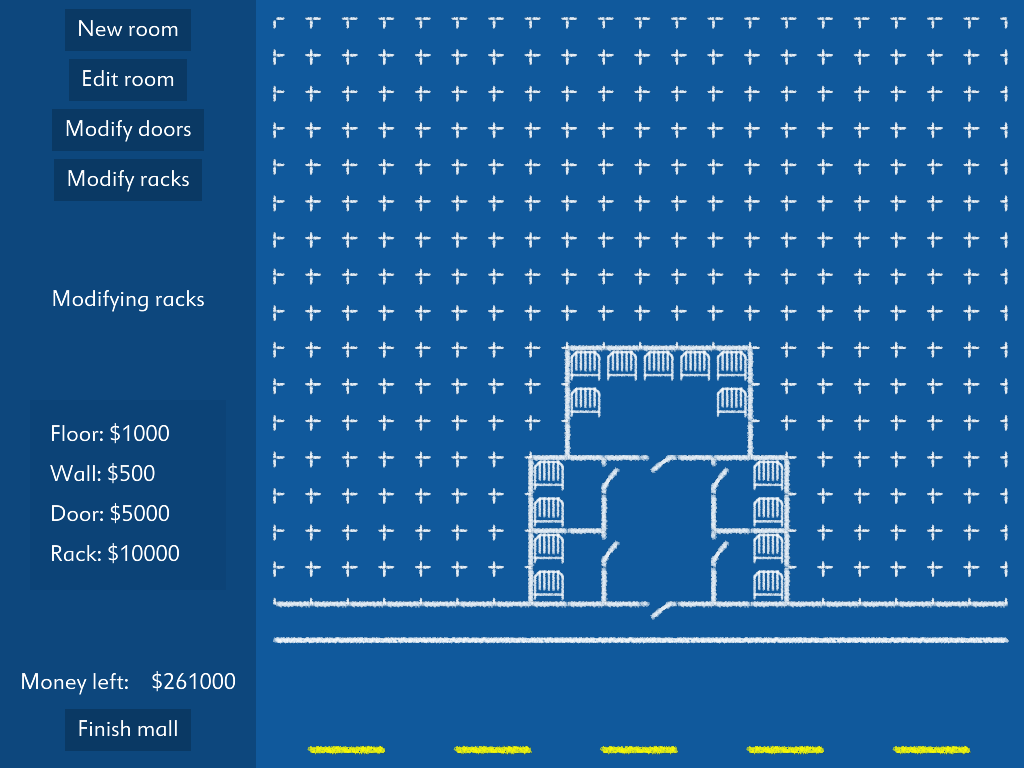

The trick for modern indie games is to come up with art styles that are beautiful for what they are. We have the horsepower to do whatever we want, but we don't have the manpower. Luckily, this is nowhere near impossible.

And Yet It Moves: A gravity-based sidescroller, with an art style based around photographs on torn paper. I can't even imagine how cheap the art for this game was, and it forms a visual style that is still nearly unique.

Darwinia: Vector-based realtime strategy game. Us coders love our simple geometric designs with hardware tricks to make it pretty – they're cheap to do and very, very effective, if perhaps a bit cliche.

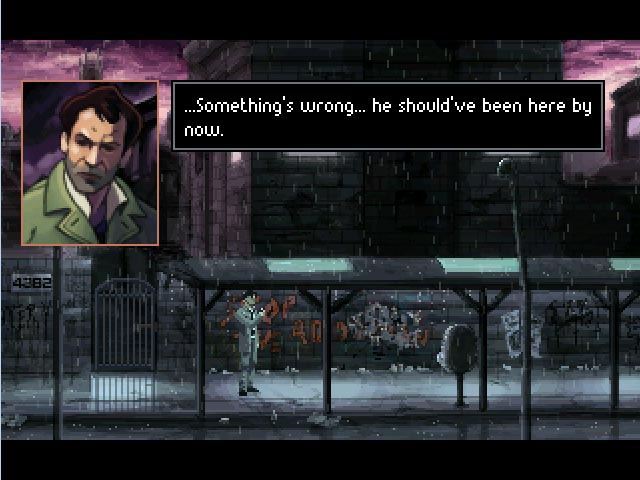

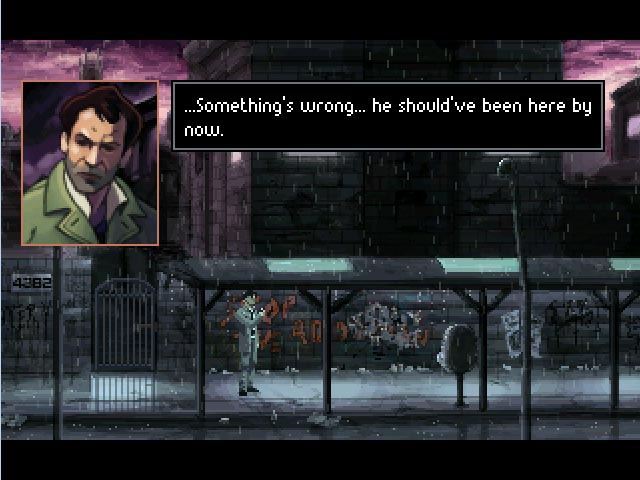

Gemini Rue: Classic Sierra-style adventure. Is it handpainted? I don't know, but it may as well be. This is a game that would fit in perfectly next to Space Quest 5.

Shatter: I did say we loved our geometric designs! Modern hardware is fast, and with the right backing behind it, that speed can be turned into prettiness without a lot of money. Particles and rendering effects are easy on the wallet and easy on the eyes.

machinarium: When you don't want to do the coding tricks, you can just do 2d handpainted art. And when you're handpainting, why bother with realism? Photorealism is a dead end for the indie developer – it's too hard to get right, and you can fall into the Uncanny Valley without even trying. Graphical style is a much better idea.

The Witness: Light and shadows are one of an indie developer's best tools, and we already visited that in Super Meat Boy. They're computationally expensive, but simple to code, and shockingly beautiful. The Witness is making great use of them, putting more coding muscle behind lighting than many AAA games do.

Design your art so that you can do it competently. It doesn't matter how technologically advanced it is. It doesn't matter how many buzzwords you can fit in. It doesn't matter whether it uses 20% or 90% of someone's graphics card.

What matters is that you know what the goal of your art is, and you choose a goal that you can accomplish.

Ten years from now, nobody will remember the games that pushed the cutting-edge of technology. Nobody will remember the games whose main selling point was how much it would overload your graphics card. The games people will remember are the games that still look good in 2020, the games that still play well even then. And those are the games people will keep buying.