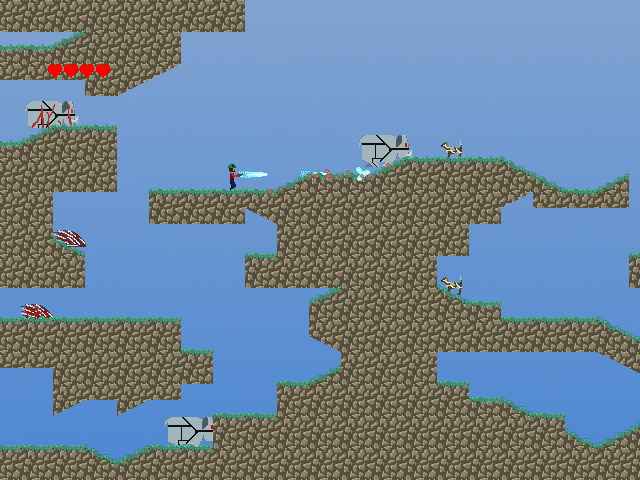

Nanok, Defender of Earth

2009, August 17th 8:24 AMHere we go again! Download installer here, or download ZIP version here.

The original Experimental Gameplay Project has started up again and I've decided to follow it. This month's theme is "Bare Minimum".

You may notice that the main character is a bear.

Get it? Get it?

Besides the obvious pun, I also applied the theme to the game mechanics themselves. Once again I'm mucking about with difficulty mechanics (I really need to stop this) and once again I've tried a new tactic (at least I'm making progress.)

At the beginning of the game you're given the option to buy upgrades. Depending on how many upgrades you end the game with, you get a better ending – the goal is to finish the game with the bare minimum of upgrades. (On your bear. Get it?) I've explicitly said "hey here is your ending, here is how you go about getting a better one" in as many places as I could. In general, people seem to be figuring it out – at least, when they put any thought into the game. A few people seem to be taking the tactic of clicking wildly, ignoring the dialog, and them complaining that they didn't get the game. I'm not sure there's much I can do about this.

What Worked

I made a level editor before starting this game. Oh man. Made everything so much easier. As part of the level editor I also put together a UI framework, which also proved invaluable – I used it for pretty much all the non-game UI to get stuff done vastly faster than I otherwise would have.

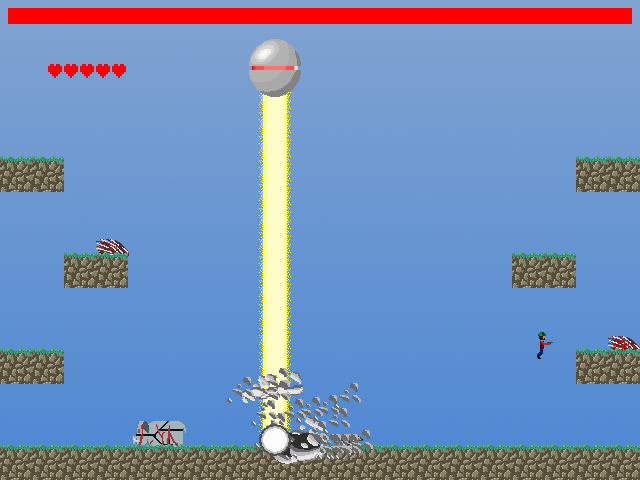

I tried a new method of doing art – sketching on paper, scanning in, and tracing the lines, then doing fills from there. It worked a whole lot better. My paper art is crummy, but it's not as awful as my non-paper art. I also ordered a small tablet, so we'll see whether that works even better for next time. I deeply love the picture I came up with for the Ringmaster.

I do have a vague, unnerving feeling that Nanok and No Such Thing exist in the same universe. They just have a similar feeling. And I'm pretty sure the Ringmaster is a major figure in that universe. He may be revisited.

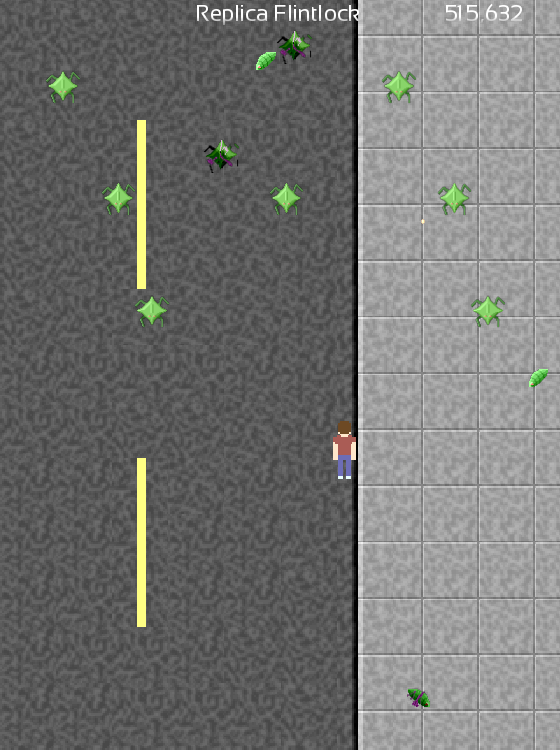

The game's fun. I actually enjoy leaping around and shooting things. I'm not sure anyone besides me has beat it on the hardest mode, so, y'know, go and try it. Tell me how hard it is.

What Didn't Work

I'm starting to push my knowledge of OpenGL rendering. That's good, because I'm learning. That's bad, because I spent probably a day or two just mucking with obscure OpenGL issues and trying to make it run acceptably fast.

While the new method of doing art does produce better and more interesting art, it's also a lot slower. I'm not sure what the tradeoff here is. Part of me thinks I should have ground out some cheap art and then done something better late, but every minute I spend working on art that I eventually replace is a minute I've effectively wasted. Not ideal. Making a game that looks and plays appropriately is really important for analyzing the gameplay value, just because of how critical graphics are, but I feel like I'm missing the balance point rather badly.

I should have put a little more work into the editor. I got it ready for this project thinking "hmm, I also want a few more features, but I probably won't need them immediately." Natch, needed 'em immediately. I spent some time working around them and some time implementing them – more things that cut into my limited time budget.

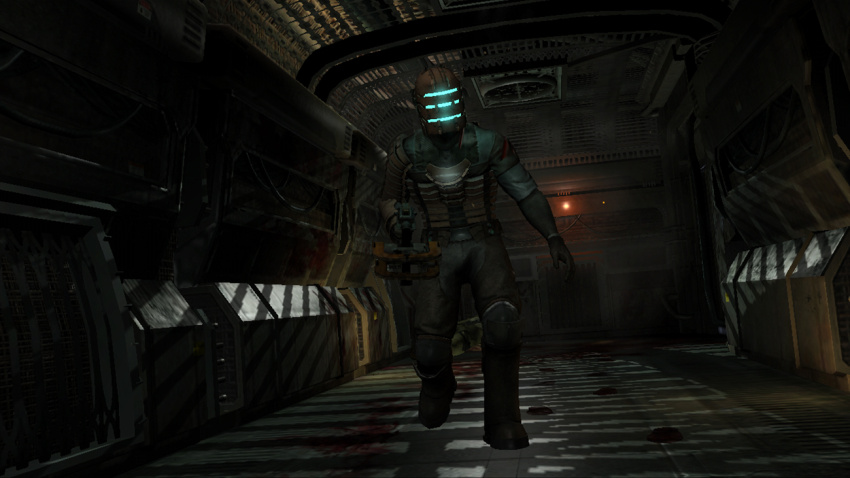

I'm not sure if I didn't prioritize well, or if I just picked up something too ambitious, or if I just got screwed by SNAFU. For the first time, I was not able to make the game I wanted to. I wanted more detail in the world, I wanted more detail in the spaceship. I did not want the player to end up walking around in a world of purple blocks. That was not my goal. And yet, here we are – purple blocks. Ugh.

I still want parallax (seriously, goddamn, I wanted that *last* game) and I also want some basic music. I don't even know where to start with the latter part.

The Bottom Line

With No Such Thing and Fluffytown I was a lot more focused than with Nanok. I need to regain that focus – when I'm making the game, the most important thing is to finish the game. Putzing around with tools and with new techniques is something that should be done before and after the week, not during the week. I fucked that up.

I'm spending way too much time with this single game mechanic and I need to go into something more interesting. I've got a few possible ideas for next game – I'll see what the game theme for next month is, then see if that inspires anything.

On top of that I think I know enough to make a longer-form game now. It's still going to be short, but it'll be a little more thorough and a little more flavorful. Yes, it will be a sidescroller. Yes, I really like sidescrollers.

Nanok is fun, but it could have been better. Still, I'm eagerly awaiting people's reactions.

And yes, this game does have some slight resemblance to Iji.