Dead Space Dissection: Quick, Look Over There, It's Less Expensive

2008, December 6th 4:20 PMGames, movies, and magic have one major thing in common – misdirection. Show people one thing, then indicate to them that they saw another, and usually they'll believe you. In magic, it's harder because they're trying to figure out what you're doing while you're doing it. In movies, it's easier because the person is really just going along for the ride. In games, it's really easy, because the player is being assaulted by zombies and doesn't have any attention to spare.

At least, they don't the first time they play the game.

The second time, they're probably paying a lot more attention to what's going on around them. The zombies attacking, yeah, sure, they're a problem – but we've dealt with them before. Let's look at the other things around us!

This is when they discover how careful the game is at showing you exactly what they want you to see, and keeping you from doing anything besides what you're supposed to.

Not supposed to go through a door yet? It's locked. Got a cutscene to watch? I can guarantee every door leaving that room is locked – even if you just came through it ten seconds earlier. You can walk through a door, have it lock behind you, and then have the very same door unlock the instant you're done with a cutscene or a movie. Happens all the time.

Sometimes they even force you to look in certain directions. Sometimes, this is to make you look at something you're supposed to see. Sometimes, this is to make you look away from something you're not supposed to see. In the first level, there's an exploding shuttle. I bet you remember seeing it explode, right? It was really cool? No! You didn't. Because you can't have. The camera is jerked away from it at the last second, and when you turn back to it, it's already exploded. You're carefully prevented from seeing the exact moment it explodes.

The reason for that, of course, is that animating something large exploding in a realistic manner is expensive and hard. It's easier to just not show it. And it works great . . . up until the person realizes what's going on and decides to try exploring the boundaries.

This is a common issue in games. There are a good number of games out there that pretend you're given choices, but actually prevent all choice. The Half-Life 2 series is a perfect example – the first time you play it feels like an exploration, but every time after that you realize, hey, wait, I'm not allowed to go anywhere else! That exploration feeling was a ripoff!

I should mention that this is not necessarily a bad thing. The fact is that most people will never start a second playthrough – in fact, many people won't even finish the first. It's arguably kind of silly to triple your budget by making content that 95% of your users will never even see. (It's also arguably not. I'll post an entry about this someday.) But it does mean that going through the game a second time is kind of like being invited backstage at a live performance, or having the magician explain his tricks – all those cute things you noticed the first time turn out to be your own fevered imagination running a bit too fast.

Solution? There isn't one, besides solving the hard AI problem and writing programs that can generate content for us. Unfortunately, this is a ways off, and if we ever do solve it, we've put ourselves out of a job.

All I can say is: be aware of it, and try hard to keep the player from feeling constrained. At least, on the first playthrough.

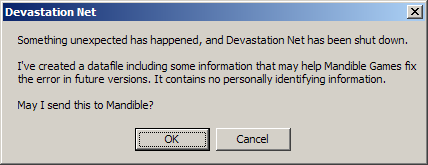

There's a lot of subtlety in a crash reporting system. For example, I've got mine rigged up so I can return messages, based on the game version, before the potentially large crash dump is sent. So if I start getting flooded with crashes that I've fixed, I can tell people to go download the new improved version, please, and stop bothering me with things I already know. (Perhaps not in those words.) Not only that but I can also return messages after the crash dump is sent, so I can analyze it server-side and return things like "your graphics card sucks" or "your RAM is bad". And it transmits the data in a compressed form to save on bandwidth, and it records as much information as I can without violating the privacy of my users.

There's a lot of subtlety in a crash reporting system. For example, I've got mine rigged up so I can return messages, based on the game version, before the potentially large crash dump is sent. So if I start getting flooded with crashes that I've fixed, I can tell people to go download the new improved version, please, and stop bothering me with things I already know. (Perhaps not in those words.) Not only that but I can also return messages after the crash dump is sent, so I can analyze it server-side and return things like "your graphics card sucks" or "your RAM is bad". And it transmits the data in a compressed form to save on bandwidth, and it records as much information as I can without violating the privacy of my users.