The Complexity Budget: Removing Repetition

2012, January 28th 10:35 AMThis is part two of this increasingly enormous writeup on complexity. I recommend reading Part One before we get started.

The concept behind this megapost really started about two years ago, when I played a pair of games that made unexpected but excellent design choices. Later, I found a third. In each case, the game removed an uninteresting mechanic that had become a staple of the genre, and in doing so, unearthed some new interesting mechanics that had gone unnoticed.

Just to warn you: two of these games don't really succeed. That's what happens when you try experimental things. But they're all intriguing games, and they all open up areas of game design that I think are worth analysis.

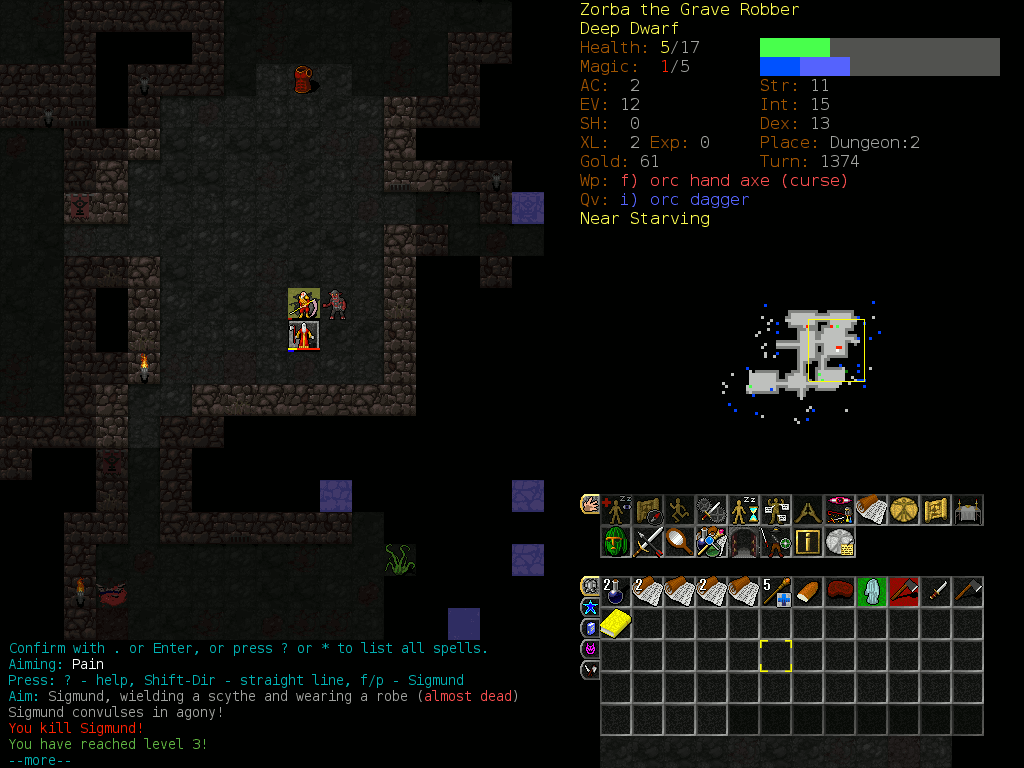

First off: Gyromancer.

Gyromancer is, at its core, a big-budget version of Puzzle Quest. Puzzle Quest is, itself, Bejeweled with an RPG grafted on. In the case of Gyromancer it's Bejeweled Twist, with a pile of surprisingly pretty art and a plotline that's . . . well, it's a plotline. We'll just go with that.

Most of the complexity of Gyromancer (yeah, we're back to complexity, you saw that coming) is tied up in your abilities, your opponent's abilities, and the effect of gems on the board. All of these have to be dealt with rather carefully. Spells can morph the board rapidly and only somewhat predictably, your opponent does quite a lot of damage when he attacks, and many of your abilities interact in complex ways.

And on top of this, you have to play Bejeweled.

Bejeweled Twist, at that, which is a more complicated variant – instead of the relatively simple block-swapping mechanic, you have to rotate a square of four blocks. It's a little harder to understand the side effects of a move and a little tougher to come up with long-term plans. Now, I'm sure Bejeweled experts will have no trouble with the mechanic, but I am not a Bejeweled expert, and I had trouble with it. The game has a lot of mechanics piled on top of each other and it was almost too much to handle.

I say "almost" because the developers made one little concession to crummy players like me. See, your cursor lights up when it's held over a valid rotation. This means that you figure out incorrect moves before you click and screw up. This also means that if you can't find the valid move, you can just skim over the entire board watching for your cursor to light up in order to find it.

In other words, they took out some of the complexity of "find possible next moves", and they moved that complexity into "choose the right ability or move to make". Being a Bejeweled expert is no longer as necessary, and training your eyes to detect valid Bejeweled moves isn't as needed. Instead, you can devote that time to choosing the right move to make.

But imagine what would have happened if they'd gone even further. Instead of telling you whether a chosen move is valid, they could simply show all valid moves. They could have removed all the difficulty of finding a move and simply left the player to figure out the best move. Even less player effort in the brute-force scanning, freeing up time and effort for the interesting decisions! I'm not going to claim this would have been a better game – I suspect I'm not the target audience – but it would have been a game I personally found more interesting. If I'd wanted to play Bejeweled, I would have played Bejeweled, but really I was most interested in the new mechanics, which Bejeweled masked.

Next up, we've got SquareLogic.

SquareLogic can be best described as Sudoku on acid. Sudoku takes place in a 9×9 grid, further divided into nine 3×3 boxes. You must fill each box with a number from 1 through 9. You can't use the same number twice in a row, or twice in a column, or twice in a 3×3 box.

SquareLogic, on the other hand, goes from 4×4 through 9×9. You're roughly limited to the same count of numbers – a 4×4 grid will take numbers 1 through 4, a 9×9 grid will take 1 through 9 – and you're still subject to the row/column restrictions. But it gets far weirder from there. First, while SquareLogic does have subcontainers, they aren't necessarily square. They might be rectangles. They might be strange bendy shapes. Worse, these containers don't care about uniqueness. They care about other things. For example, you might have a 24x container, which means that the product of the numbers within the container must be 24. Maybe that's 1*2*3*4. Maybe that's 1*1*4*6. You might think it could be 2*2*2*3, but you'd be wrong – remember, you can't have the same number duplicated in a row or a column, and there's no way to lay out 2*2*2*3 such that no two 2's share a row or column. But 1*1*4*6 would fit in an S-shape, with the two 1's on opposite ends.

That's not all, though! SquareLogic doesn't tell you where the containers are. You're given one square in each container, and the rest of the container locations have to be derived logically. Sometimes that's easy: if the container is "12x", you know it needs to be at least two squares large. Sometimes that's tougher, though: is "12x" two, three, or four squares?

And then, just when you feel confident in that, SquareLogic throws double-board puzzles at you. Two boards, the same solution on each board, but different containers. You'll have to solve them simultaneously to win, as neither board has enough detail to get a full solution.

All of this could easily become overwhelming. In fact, just the busywork could be overwhelming – Sudoku-style games require that you keep track of which numbers have been used in which rows or columns. But SquareLogic, after throwing an enormous amount of complexity in your face, quietly shuffles much of the busywork away and takes care of it for you. Each box contains, greyed-out and in small type, all possible numbers that could fit there. You can eliminate numbers manually by right-clicking them. But if you make a decision and place a number in its final location, SquareLogic instantly clears all instances of that number from that row and column, as you can guarantee the number won't show up in any other similar places. The busywork is boring, and the computer can do it, so why shouldn't it?

SquareLogic helps in other ways. If you mouseover a container, it will list all possibilities. Mousing over 12x will show 3*4, 1*2*6, 1*3*4, 2*2*3, 1*1*3*4, and 1*2*2*3. If you've determined that your 12x container is only three squares large, it will restrict that down to 1*2*6, 1*3*4, and 2*2*3. If you've shown that none of the squares can contain a 3, it will cross out 1*3*4 and 2*2*3, leaving you with just 1*2*6. Sure, you could do it by hand, but does anyone want to spend their life trying to factor numbers?

(Especially the larger numbers – multiplication containers can easily reach the thousands, as 6*7*8*9 = 3024. I don't want to factor 3024. That's why I own a computer.)

The end result is a horrendously complicated, but surprisingly manageable, puzzle. When you get stuck, it's usually because you missed something clever, not because you misclicked or forgot to cross out an option. Since the game keeps track of all the little mental details for you, your brainspace is available for the far more interesting logical derivation.

But it's worth noting what SquareLogic didn't automate. SquareLogic will never actually choose a number for you, even if you've eliminated all alternatives. SquareLogic will happily tell you that there's only one possibility for a container, but it will never narrow down the elements in that container without your explicit input. The automation is solely limited to removing row/column conflicts and informing you about container possibilities. If you go too far, you end up writing a game that plays itself. SquareLogic went further than most do, but not too much further, opting to stay back and leave the fun bits up to the player.

Last, though with unarguably the highest budget of any of these games: Final Fantasy 13, and specifically, FF13's combat system.

(Before I continue: no, it hasn't escaped my attention that all of these games either involve squares or are made by Square. I promise this is a coincidence.)

From Final Fantasy 1 all the way through Final Fantasy 10, the most fundamental assumptions of Final Fantasy's combat system remained unchanged. You controlled a party of characters, from one to four at a time. Each character had a number of abilities, generally including Attack, Magic, Item, and a special gimmicky thing. Each character attacked in some order – generally determined by the character's speed – and used a single command at a time to damage the enemies, heal friendlies, or cast helpful (or harmful) spells. The enemies did the same, interspersed with your units.

There were many variations, of course. Some games used an "active time battle" system where characters attacked somewhat in realtime, although this was essentially a realtime wrapper around a turnbased game. For a while, every Final Fantasy game came up with a new way to gain magic, from Espers to Materia to Guardian Forces to the Sphere Grid. In FF7, your characters' spells were highly customizable before battle. In FF10, your characters could be swapped out at a moment's notice in a fight. FF8 let you buff your characters by "attaching" spells to them. It got complicated. But the fundamental design didn't change – one character took their turn and did something, the next character took their turn and did something.

FF11 broke the pattern by virtue of a genre change. FF11 was a massively multiplayer game, where you controlled a single character, and your party fought as a cohesive, realtime group. The gameplay didn't surprise anyone, at least after the MMO layout was announced – MMOs don't work with the old Final Fantasy method. But FF11 heavily influenced FF12. In many ways, FF12 felt like a single-player MMO. Instead of controlling a party, you directed a party – you wrote general-purpose scripts to automate what you intended, then gave direct commands to your characters when you needed to override their behavior.

Which taught us some very curious things. It turns out that the old Final Fantasy combat style is, fundamentally, very repetitive. Classic Final Fantasy combat consists of three things: healing, buffing, and attacking. First, make sure nobody's about to die. Then, cast the spells that make your characters vastly better. Finally, kill the bad guys. Most of this can be automated. In fact, the only part that takes any thought is "attacking", as various monsters require different attack spells. For example, robots are vulnerable to lightning, so if you're fighting robots, hit them with lightning. That's all the thought you need to put into it, though – after you've figured that bit out, it tends to be quite formulaic.

When FF12 automated all the basic bits, they were able to use that freed-up gamespace and make the bosses more complicated.

Now, FF12 didn't do a great job of it, because in order to play the game efficiently you basically had to be a programmer. Your characters had little automated scripts that you had to design. If you weren't good at that kind of process design, you sucked at the game. But FF13 took this to another level altogether.

In FF13, you didn't really control your characters at all. Instead of telling them what to do, you told them how to behave. For example, you'd tell one character "be a healer", and that character would start lobbing heal spells around to keep everyone else alive. You'd tell another character "cast buffs", and that character would automatically choose appropriate buffs and keep your party fully augmented. At the same time, FF12 took the old three-role Final Fantasy system and split it into a whopping six roles. The "buff" role was joined by a "debuff" role. They picked up a fully functional tank role, able to absorb firepower and take minimal amounts of damage. And, in a rather uncommon twist, "damage the bad guys" was split into two separate roles – a Ravager that gradually knocked the enemy off-balance, and a Commando that did enormous amounts of damage, but only once the enemy was off-balance.

Now, you did have direct control over one character, but to be honest, most of the time you just mashed the "do whatever you would normally do" button. The AI was smart enough to prioritize buffs intelligently and it understood which debuffs worked on the enemy. The tank would do a good job of keeping damage contained, the healer would distribute healing spells appropriately, and the various damage roles would quickly figure out the right spells to use and . . . well . . . use them. Instead of spamming Lightning on the robots, you watched while your characters spammed Lightning on the robots.

And as you'd expect, this opened room for more complicated bosses. Bosses in FF13 are truly deadly – a few turns of the wrong actions will often result in a party wipe and a game-over. Your characters will respond quickly, and do an amazing job of efficient damage mitigation and recovery, leaving the only real in-battle decision to a moment-by-moment choice between party roles, deciding on the fly which combination of roles will prevent your party from dying and kill the boss.

Which is, in many ways, where FF13 fails. You simply don't have enough choices. I'm all for automating the repetitive parts, but it turns out that the Final Fantasy combat model is repetitive parts. When you take away all the repetition, and don't replace it with something new, you're left without a game. In the case of Final Fantasy, the "game" becomes recognizing the right response to half a dozen boss abilities. When boss does this, you mash Tank button. When boss does this, you have time to rebuff. When boss does this, you can go back to kill mode.

The problem is that the roles are very, very specialized. If you need a tank character – and you often do – that's a full third of your party's functionality tied up. If you need a healer as well, that's another third. That leaves you with one character left to do damage, and that's only if you don't need buffing or debuffing. The game stops being about fighting the monster and starts being about juggling role timings.

Which is admittedly an interesting mechanic. Perhaps not one that stands on its own, but one that could be used as part of a much better game. And a mechanic that simply wouldn't have been uncovered without automating all the boring parts of combat.

So, what's the conclusion to all this?

I've talked about three games that got rid of large parts of their complexity. In the case of SquareLogic, I think it was a clear win. In the case of Gyromancer and FF13, I think it was a bit more dubious as a game, but quite valuable as research. The real lesson is that removing obvious sources of complexity does not always result in a better game, but it does usually result in learning more about your game and finding unexpected deposits of fun deep inside your game's emergent behavior. Even if you don't want to do it in your final release, it may be worth trying it out as an experiment, just to see what you discover.

And that neatly segues into our third entry, in which I'll compare pairs of games to see how differences in complexity layout can result in vastly different gameplay. I'll see you again next time. :)